For those that do not otherwise have access to the Weekly Tax Bulletin, a further recent article by View is extracted below.

As previously reported by us in the Weekly Tax Bulletin, there are a range of issues often overlooked in relation to trust distributions (see 2014 WTB 43 [1426]) and extensions to vesting dates (see 2014 WTB 44 [1446]). Rarely, however, do these issues arise together in the same factual scenario.

In the lead up to another 30 June, the decision in Domazet v Jure Investments Pty Limited [2016] ACTSC 33 (7 March 2016) is a timely example of the problems that can arise when a deed is not carefully reviewed before trust distributions are made.

The decision

In summary, a Family Trust was settled in the ACT on 1 April 1980. The Family Trust deed gave the trustee the power to nominate additional beneficiaries, including trusts, so long as the vesting date of the other trust was not longer than that of the Family Trust.

In 2009, a new trust (referred to as the "Finance Trust"), which was part of the same family group was purportedly appointed as a general beneficiary of the Family Trust.

The Family Trust had a cascading optional perpetuity period, which the parties wrongly interpreted as allowing the vesting date to be 80 years from the date of settlement. In fact, the Family Trust vesting date was 21 years after the death of King George VI's living issue as at 1 April 1980.

The Finance Trust, established in 2005, was set to vest either upon the election of the Trustee or a maximum of 80 years from settlement, making it prima facie ineligible. In an attempt to ensure the Finance Trust was an eligible beneficiary of the Family Trust, the vesting date was then amended to be one day before 80 years from 1 April 1980 (ie 31 March 2060).

Practically speaking, this meant that in order for the Finance Trust to be an eligible beneficiary of the Family Trust, it needed to be absolutely certain that at least one of King George VI's living issue in 1980 would still be living on 31 March 2039 (that is, 21 years before 2060), which the Court thought was possible, but not absolutely certain. This meant the appointment of the Finance Trust as a general beneficiary was invalid.

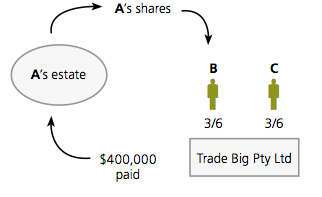

It appears from the decision that a number of capital distributions were purported to be made after the Finance Trust was invalidly appointed as an additional beneficiary. The invalid appointment meant that the distributions made to the Finance Trust would have been done in breach of trust. Furthermore, the invalid distributions would have also caused adverse tax consequences for the parties. This seems to have been a potential issue because the ATO had made submissions as part of the proceedings.

Perpetuity rules

It is critically important to not just read the deed, but also specifically consider which perpetuity rules apply. The difficulties arose in this case because amendments to the rule against perpetuities were progressively rolled out throughout Australia. The advisers which prepared the documents had wrongly assumed the ACT rules, which came into effect on 18 December 1985 (after the Family Trust was settled), were implemented at the same time as the Queensland rules were introduced (1 April 1973).

In this respect, the earliest change to the rule against perpetuities occurred in Victoria in 1968, whereas Tasmania only introduced new rules in 1992. When reviewing trusts which span between these dates, it is therefore critically important to firstly determine the trust's governing jurisdiction, but also consider which perpetuities rules apply.

Some possible workarounds

With the aid of hindsight, there were a number of alternatives that could have avoided the outcome that the parties ultimately faced: a substantive trust to trust distribution being invalid. In summary, the other alternatives that could have been adopted include:

- The vesting date of the recipient trust could have been amended to provide that - notwithstanding any other provision of either trust instrument, it would automatically vest on or before the date of the distributing trust.

- The requirement in the distributing trust that the recipient trust needed to vest before it could have simply been deleted. While it still would have been necessary for the recipient trust to have ultimately vested by the date of the distributing trust, it would have been possible to rely on the 'wait and see' rule rather than the distribution being void immediately on the date that it was made.

- Depending on the factual matrix, the distributing trust could have made a distribution directly to the ultimate intended beneficiaries, even if that may have required a variation to the trust instrument (and thereby avoid the need to distribute to an interposed trust).

In regards to the "wait and see" rule, the approach to be taken was summarised in the case of Nemesis Australia Pty Ltd v FCT [2005] FCA 1273 (14 September 2005) (reported at 2005 WTB 40 [1638]). The case confirmed that the "wait and see rule" in each jurisdiction can be relied on in a situation where a trust distributes to another trust with a later perpetuity date.

The "wait and see" rule means the initial distribution will not be void when made, and will not become void until such time as there is a failure to distribute out of the recipient trust before the vesting date of the original distributing trust.

Rectification

The final main alternative to the issues faced in this case, which was the one ultimately adopted, was to seek rectification of the documentation from the Court.

The case provides a very detailed analysis of the way in which the rectification rules work, including heavily quoting Dr Spry, who has been featured prominently in trust related areas, both for his academic writing and his legal challenges in a personal family law dispute (see Kennon v Spry (2008) 238 CLR 366 (reported at 2008 WTB 51 [2303]).

Ultimately, although with some reservation, the Court did rectify the relevant documents to essentially adopt the approach outlined at paragraph (a) above. While it cannot be certain, it is likely that the rectification order settles a number of the potential taxation consequences resulting from what would have otherwise been invalid distributions.